The mere fact that we live means that we allocate our allotted time on the planet to various activities. Even though we may have myriad alternatives as to what we could do with our time at any given moment, most are mutually exclusive. For instance, as I’m writing this, I’m not able to do anything else at the same time. In other words, I must choose this activity and let others go by. This internal zero-sum game we’re forced to play makes time our scarcest resource.

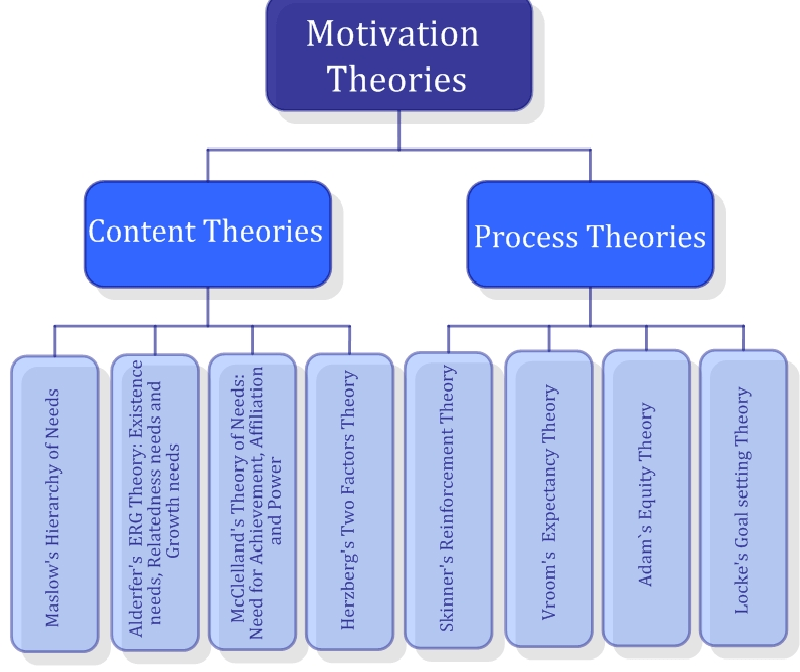

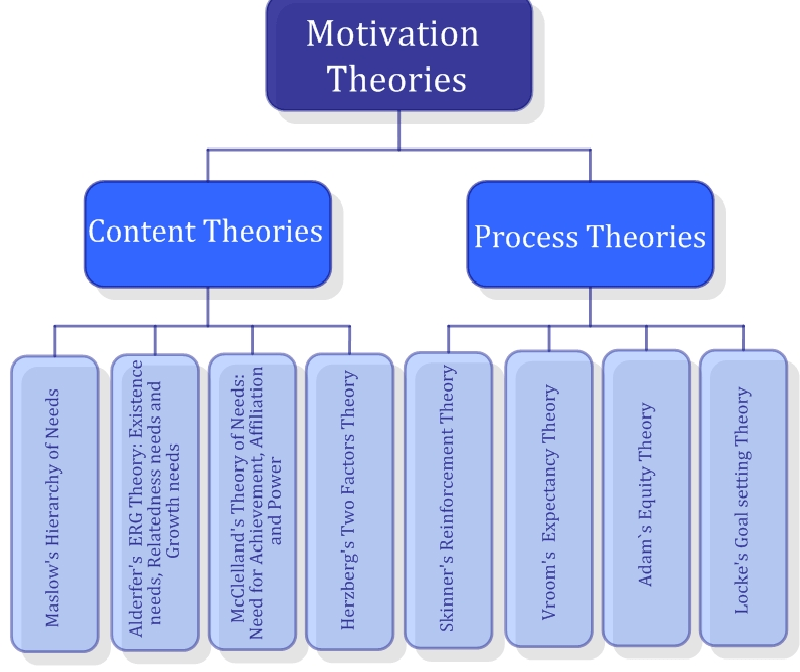

As distasteful as playing the game may seem, we do have to take responsibility for our decisions about how we use our time or the resource slips away and we risk regret over lost opportunities or, worse yet, we find our lives imperiled. Such responsibility taking is at the heart of why we do what we do when we do it. Human motivation is the longstanding subject of ongoing research, study and analysis resulting in a number of theories to explain it. The following diagram from Psychology by Juliánna Katalin Soós and Ildikó Takács (2013), identifies several of the more prominent ones.

For the purpose of this post, Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is the theory of choice because is well-known, easy to understand, and widely accepted as a framework for examining human motivation (see diagram below). It can become the basis for each of us to consider in how we spend our 700,000 hours.

Maslow’s theory suggests that under natural circumstances we would divide a 24-hour period into thirds with one-third dedicated to sleep – an essential physiological need about which we are only now beginning to understand the degree of importance it holds, (see Why Sleep Is Important), another third to the remaining basic needs we all have, and the final third to achieving an improved quality of life the characteristics of which are unique to each of us.

The diagram below positions Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in between a couple of ways to carve-up a 24-hour period in relation to it:

The left-hand time stack, entitled Work-Life Balance, shows three equal 8-hour segments in keeping with the “natural” division of a given 24-hour period described above. While an even split may seem idealized, the intent is to emphasize the importance of a balanced allocation of one’s time as the foundation for a healthy and satisfying life. Just as successful personal finance strategies emphasize the importance of investing in a diverse portfolio for better long-term results, balancing one’s daily life offers the best return on investment for one’s 700,000 hours.

The right-hand stack, entitled Koyaanisqatsi – the Hopi word for “unbalanced life” – illustrates a disproportionate allocation of time in a day to meeting basic needs. The result is that one must make trade-offs between sleeping less in order to have some modicum of quality of life or sacrificing higher aspirations altogether in exchange for longer sleep. Regardless, an unbalanced life inexorably becomes one that is unhealthy either physically or psychologically or both. And this condition is frequently a point of discussion and debate among those who study it, suffer because of it, offer relief from it, and even contribute to it as mentioned in these articles: Is the Stuff You Buy Over 20 Years Worth 40,000 Hours of Time? – The New York Times and Buying Time, Not Stuff, Might Make You Happier : Shots – Health News : NPR.

So, how does your life stack up? Does it matter in how you make your decisions about how to spend your time from one day to the next? If it does matter and you want to change it, how will you go about doing so?