My previous post, Local Timebanking, introduced The Five Core Values of TimeBanking by Edgar Cahn. These organizing principles define the role timebanking plays, both as a platform and set of processes, to account for one’s time invested in “forms of work that money will not easily pay for, like building strong families, revitalizing neighborhoods, making democracy work, advancing social justice.”

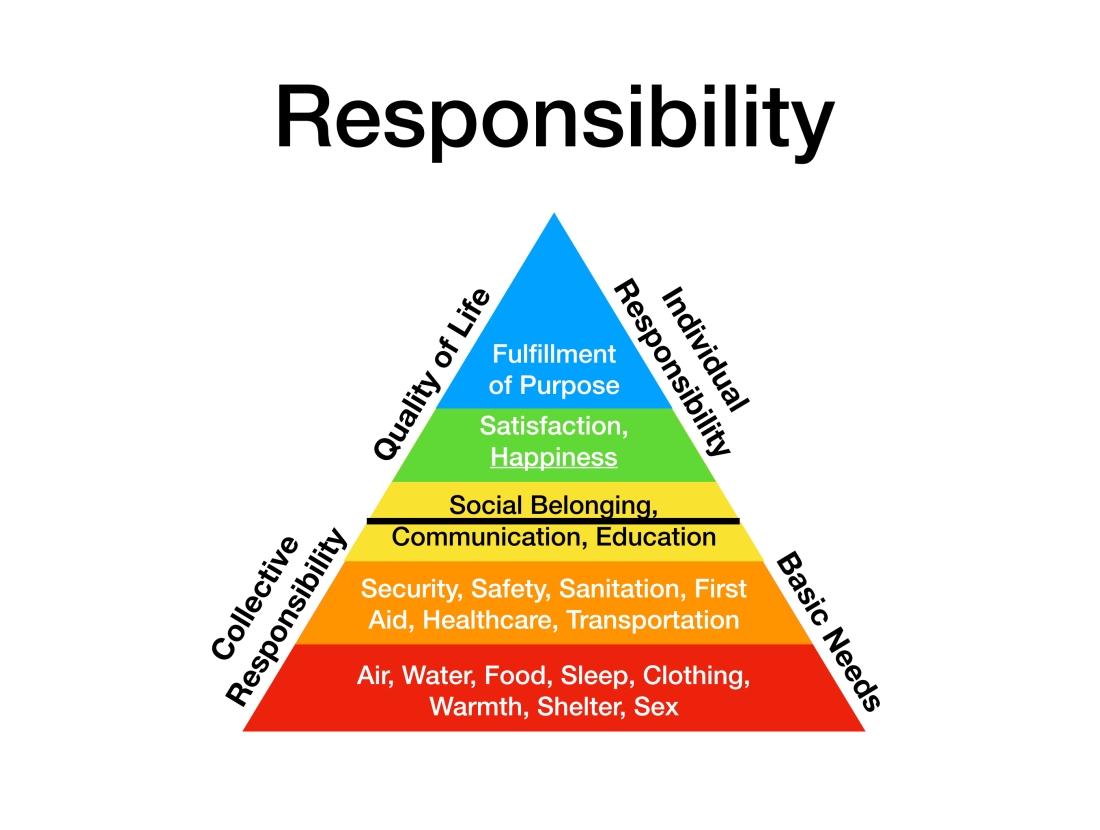

In the context of Maslow’s Hierarchy, timebanking helps community members take collective responsibility to assure the basic needs of all members are met. Then, with basic needs in place for all, each member is better positioned to take individual responsibility for personal needs related to quality of life.

The rendition of Maslow’s Hierarchy below illustrates more specifically what community members take responsibility for, individually and collectively:

Key takeaway: the more a community provides all its members with their basic needs, the higher likelihood that individual members will enjoy a higher quality of life by whatever subjective factors each chooses.

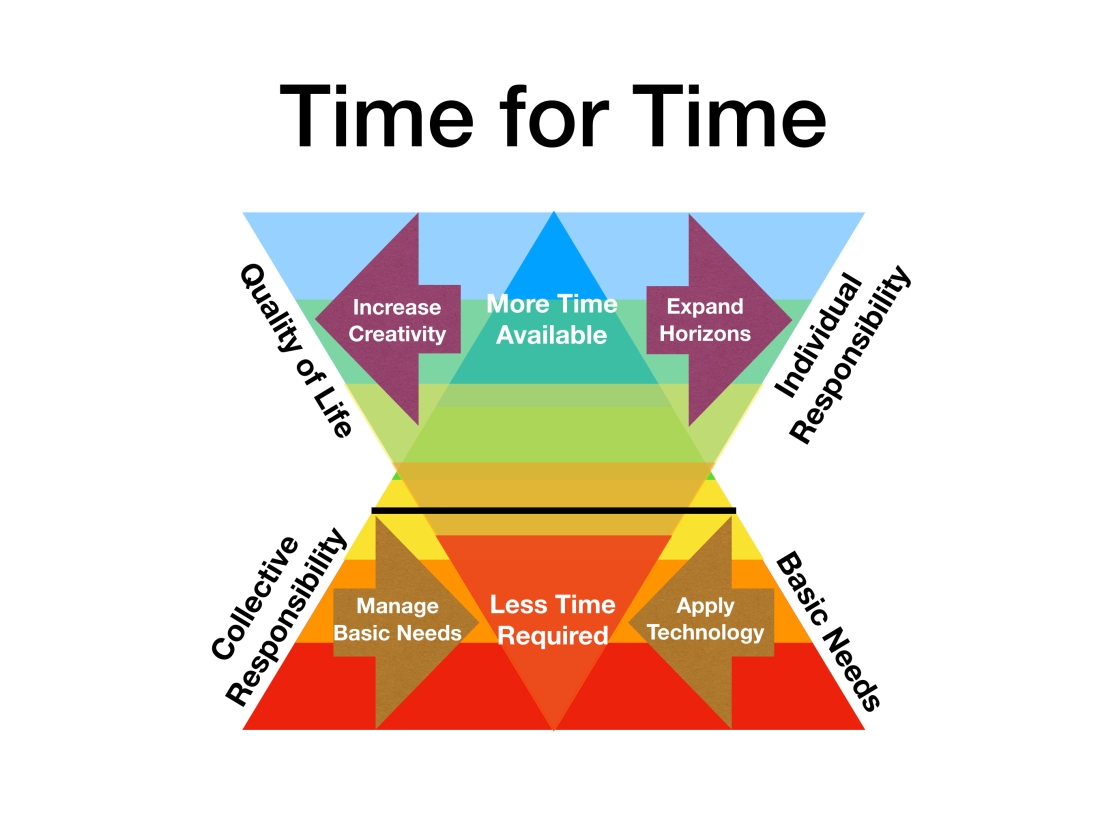

In effect, communities that honor this commitment decrease the amount of time its members must dedicate to meeting their basic needs which results in them having more time available for quality of life endeavors.

The post, Time Beyond Basic Needs Builds Human Capital, makes the point that more time consumed above the line in the “quality of life” zone has the social benefit of increasing human capital. In other words, it turns Maslow’s Hierarchy upside down so that more time could be dedicated to pursuits beyond basic needs. The diagram below — a variation on “The Human Enigma” graphic in the post referenced above — highlights how the dynamics between the two hierarchies impact a community and its members:

The community takes collective responsibility to manage the accessibility, availability, and affordability of basic needs for all community members. To be successful, communities develop strategies and underwrite projects along a localization — globalization continuum to assure needs can be met and minimize risk to member for failure to deliver.

In addition, the community applies advances in technology to the flows of basic needs in order to reduce costs, increase control, and relieve community members from onerous tasks. Effectively, this shifts what community members do with their time from activities below the line to those above the line — time for time — which increases their creativity and expands their horizons. The subsequent uptick in human capital benefits the community, internally, as well as individuals and organizations in regional and global interrelationships.

Key takeaways: Timebanking provides the opportunity for community members to account for the time they invest in projects related to management of basic needs and application of technology. It also enables members to exchange time credits they receive for participating in these projects so they can shift their attention from below the line to above the line endeavors. Furthermore, documentation of the cumulative time invested, exchanged, and consumed by community members establishes a demonstrated value of time and skills that incentivizes other individuals and organizations to become timebanking members and offers collateral in proposals to funding agencies.

In upcoming posts I will explore these in more detail with examples from local timebanks. Stay tuned…