Diversity is closely linked to organization effectiveness and feeds the dynamics associated with garnering social power, distributing authority, and exercising leadership. Ross MacDonald, introduced in previous blog postings here and here, and Monica Bernardo co-authored a recent paper published in the Journal of Developmental Education, Fall 2005, Vol 29, No 1 highlighting their research on “diversity” and “ground truth.” Ross is warmly welcomed back to this blog to draw from his and Monica’s paper about this key topic. Ross, the floor is yours…

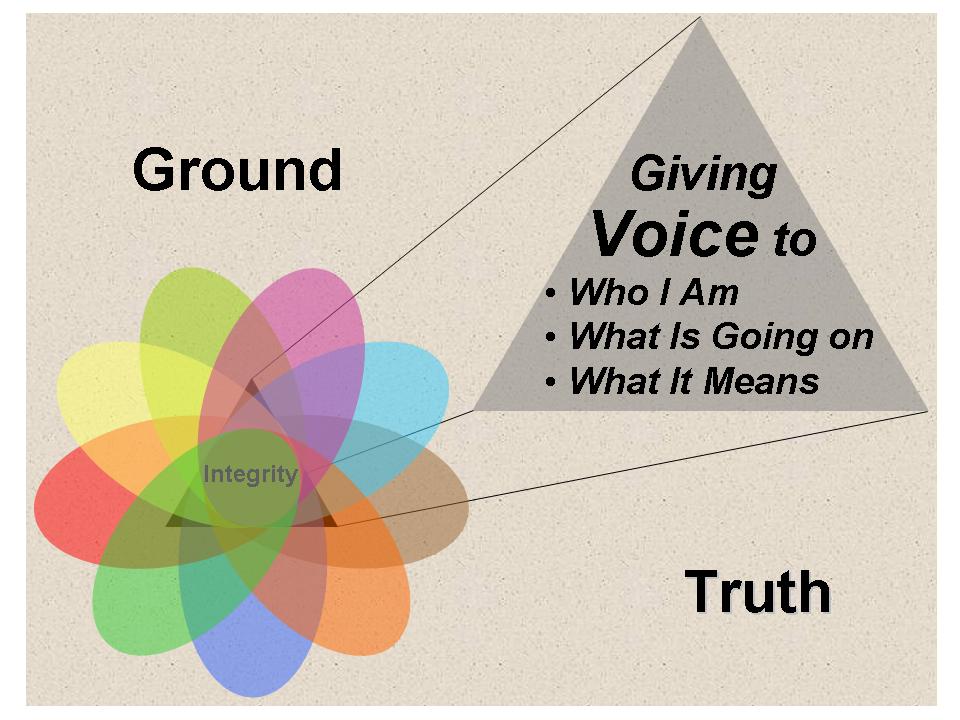

In previous articles about ground truth, I highlighted the importance of attending to multiple perspectives. In this entry I consider the issue of how well we listen to and to what degree we value multiple perspectives by focusing on the catch phrase, diversity. Nearly every organization must consider issues of diversity. Weighing in on diversity are federal mandate, state law, judicial threat, moral authority, public pressure, and pressure from employees. Clearly, leadership in any organization must consider “diversity issues.” Whatever that means. And that’s the problem as I see it.

Too many discussions about diversity fail to consider what it is we are talking about. In so doing we make diversity issues an onus and not an opportunity. We have typically answered the call for diversity by attending to the most superficial features of skin tone and gender and by trying to up the numbers of the under-represented. In so doing, we delude ourselves and others that a “head counting” approach is both powerful and meaningful. After all, it is easier to vary the color of faces than to listen closely to their experiences and alter our thinking about the complex dynamics of difference that play out among us. An exclusive focus on placing people into a set of categories based on gender, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and so forth blinds us to the less visible and more complex dynamics of diversity of which we all are a part.

The problem is that this is a convenient kind of blinding; it allows us to assume that because we have satisfied a numbers requirement, we have achieved diversity. While adding people to the mix certainly has intrinsic value and moral force, we must consider what happens in that mixing. How are people interacting? How are those satisfying diversity numbers being positioned and perceived? Pursuing these questions in good faith and with open minds increases organizational capacity. Wouldn’t that kind of understanding be immensely useful to any organization looking to enhance employee relations, heighten team productivity, and serve a broadening customer base?

Therefore I propose that we pursue diversity as a continually expanding knowledge about the dynamics of difference. Considering diversity as a dynamic of difference requires questioning how we perceive, value, and act on differences among us in our organizations and communities.

Recent advances in astrophysics provide an apt analogy for understanding the dynamic of diversity. In studying the universe to search for the origins of energy and life, astrophysicists traditionally have relied almost exclusively on what they could see — visible light and its properties — to explain the universe and its workings. Similarly, in our work and social environments, traditional thinking about diversity also has attended to what we could most conveniently see, variations in skin tone and gender, to understand the complex workings of our social and organizational universes.

Now, however, astrophysicists have inferred the presence of invisible matter and invisible energy. Invisible matter is believed to be a key underlying dynamic of the phenomena of gravity. Invisible energy exercises forces so powerful as to compel the continuing expansion of the universe. Once scientists attended to their own false assumption that there was nothing there, they saw that there was in fact a great deal operating outside their view of the world. Once they attended to those things and their operations, their understanding of the dynamics of the universe changed dramatically. For an example, click here.

Similarly, the seeming invisibility of complex energies surrounding the dynamics of difference should not lead us to falsely assume that there is simply nothing there. Like invisible light and invisible matter, these dynamics of difference are very much a part of our world, representing little-understood forms of energy which, if understood more thoroughly, could propel organizations to greater understanding, acceptance, and profit.

What are the implications of the dynamics of difference for communities and organizations? We must first recognize that those who stand out when we count heads are very likely minorities and thus subject to daily uncertainty as to when ill-founded judgments are being made about them. In my thirty years as an educator who focused on programs for nontraditional students, I heard story after story about the uncertainty of daily life. Did the store owner ignore me because of an automatic belief that I have no money to spend? Conversely, am I being followed in the music store because the employee thinks I am going to steal something? Are my children being tracked into lower expectation classes because of their skin color? In my work with organizations I have repeatedly heard questions such as the following: Am I being positioned on this work group because of my skills and knowledge like everyone else or is my skin tone being positioned to create the look of diversity? Does hiring an affirmative action officer deeply invest all employees with acting affirmatively or does it allow them to shift responsibility solely to the office of affirmative action?

Yes, these actions happen daily. Yes, there are situations which may look like these where there is no malice but still the harm. And yes, some situations lack both malice and harm. But it grinds on people to deal daily with the uncertainty and to have those who don’t deal with these uncertainties discredit reports of that experience. This daily uncertainty is a fundamental part of being different but is less detectable and thus believed less credible by those in the mainstream. Therefore an important part of the dynamic of diversity is that those who are perceived as different must daily try to navigate these situations and deal with the uncertainty presented to them. Click here for a wide range of resources.

Many of those not perceived as different just don’t understand this. Their detectors are not calibrated for this subtle dynamic. They can justifiably condemn the dramatically evil and violent acts stemming from prejudice in cases such as Matthew Shepherd and James Byrd Jr.. In contrast, however, the day-to-day grind of being different is not as easily detected by those who haven’t lived it. Like previous astrophysicists, they have falsely assumed that because something wasn’t visible to them, there was simply nothing there. Yet the presence of those moment-to-moment reminders of difference and the on-going uncertainty about whether those judgments are at play in any given circumstance are key components of the dynamics of diversity. We must therefore attend to them.

Moreover, attending to this dynamic creates opportunities to position people’s heretofore invisible energies in ways advantageous to the central purposes of an organization. Why is it that, when a major bank hires Spanish-speaking tellers in its branches in Spanish-speaking communities, its customer base expands? The obvious, easily seen reason is that the teller and the customer are of the same culture, speak the same language, and can therefore relate. Following that logic, a bank should identify languages spoken in various communities and hire tellers accordingly. Is this really possible? Consider that in Southern California’s 181 school districts and 2,000 public elementary schools, more than 90 languages are spoken.

But is there more to it than language? Is it a kind of resonance which is communicated from the teller and believed by the customer – an understanding of what it is for an outsider to access the bank and of how to make a smoother connection between the bank’s resources and its customers’ needs? Is it a kind of “seeing” of that customer that others don’t? Suppose these and other factors other than language are at play and can be trained in tellers, loan agents and branch managers? If so, then it would certainly benefit the bank to invest all employees in connecting with the customer base just coming into view. We will only know if we ask the question and peer into the less visible light.

In both the universe and the workplace, there is much to be learned from what we haven’t seen. A critical step is to recognize the limitations of one’s vision – in the case of astrophysics, the limitations of telescopes and mathematical models — and in the case of organizational leadership, the limitations of identifying diversity based only on that to which we have historically attended and is most easily seen. In the same way that scientists gained tremendous insight by gazing into those formerly invisible areas of space, so might we see the ‘invisible’ dynamics by gazing into the less seen areas of marginalized people’s experiences — if we simply direct our attention there. Understanding these ground truths and shaping them into positive assets increases social cohesion and business productivity.

Originally posted to New Media Explorer by Steve Bosserman on Sunday, February 19, 2006