Time matters for each of us whether unpaid or not. Reducing our individual time on the planet to a binary expression between paid and unpaid shortchanges the value we bring to our common humanity during our lifetimes. This raises a couple of questions for consideration in this post:

- How to measure the value of unpaid time?

- How to pay the provider for this value rendered?

In my previous post, Unpaid Time Distribution, I noted that unpaid time can be voluntary or involuntary. Examples of the former include a leave of absence from paid work, participation as a volunteer or intern within the public or private sector, or a lifestyle decision to live “off the grid.” As the wording suggests, involuntary unpaid time is not necessarily an outcome of choice, but the result of unemployment and unavailability of paid time due to termination, reduction in force, early retirement, sour reputation, etc.

Regardless of being voluntary or involuntary, unpaid time remains unaccounted for in contrast to paid time where value can be measured by productivity and profit. If unpaid time has value how does one generate and measure it? The diagram below, “Value of Unpaid Time,” gives us a way to look at it:

The left side of the diagram below lists items we use to spend our unpaid time: cell phones, computers, devices (includes Internet of Things), games, apps, and GPS to name the more obvious ones. The right side lists the data we generate by using the aforementioned items: identity, location, behaviors, connections, content, and access and myriad variations on each. Organizations in the public and private sectors use these streams of data to increase profits, pacify populations, and concentrate wealth. In other words, they capture, measure, and realize the value generated by us during our unpaid time activities.

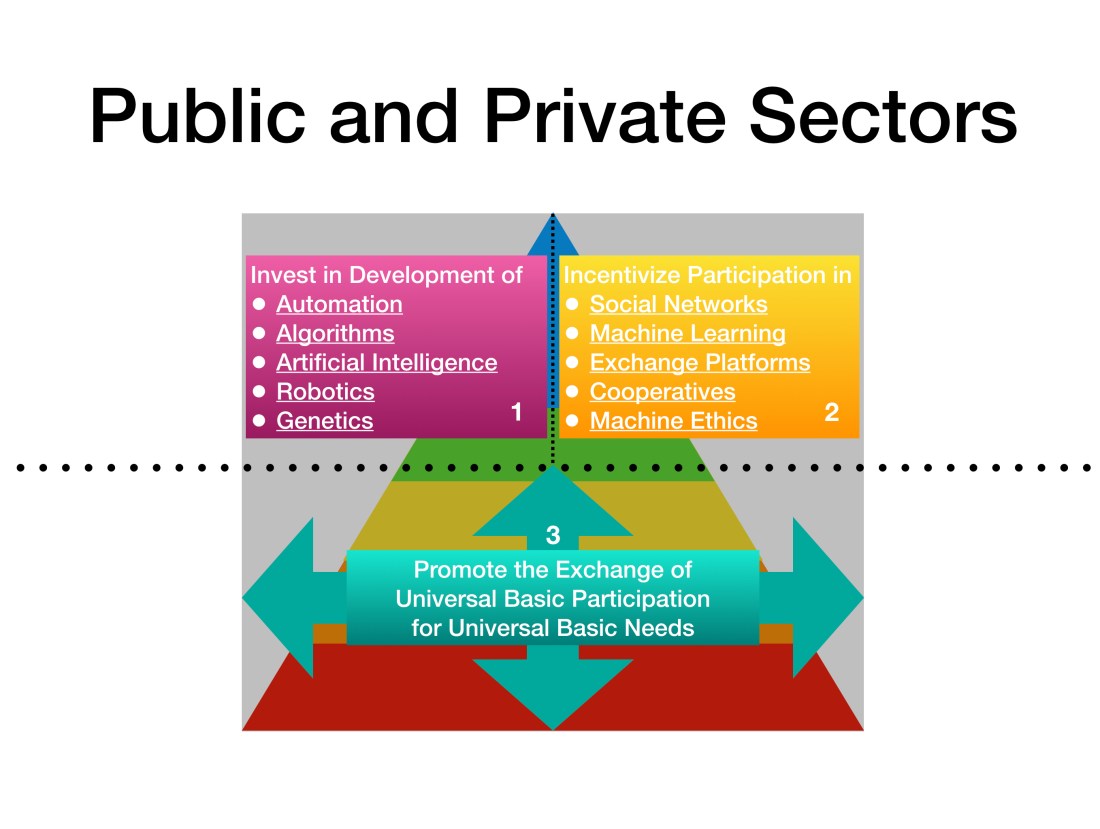

So important is the data we generate that organizations in both the public and private sectors vie tirelessly for our attention. The diagram below, “Public and Private Sectors,” illustrates some of the resulting dynamics:

These entities combine investment in the development of information and knowledge technologies (section 1) with sophisticated interface designs and structures to incentivize our participation (section 2) so that the resulting data streams are plentiful, wide and deep. In effect, we humans become living sensors who generate data through social networks, machine learning, exchange platforms, cooperatives, and machine ethics that can be put to use by automation, algorithms, artificial intelligence, robotics, and genetics.

Ideally, all of us would be plugged in 24/7 – a kind of universal basic participation that generates a lifelong stream of data about us and for us. The incentives would go beyond gamification and dopamine rushes to payment in the currency of basic needs. In other words, we would allow data about us to be captured by the machine on a continuous basis in exchange for our universal basic needs of food, water, clothing, housing, energy, safety, security, healthcare, education, socialization, etc. (section 3).

The issue isn’t that the value of unpaid time can’t be measured, it’s that it’s not paid.

And if it is paid?

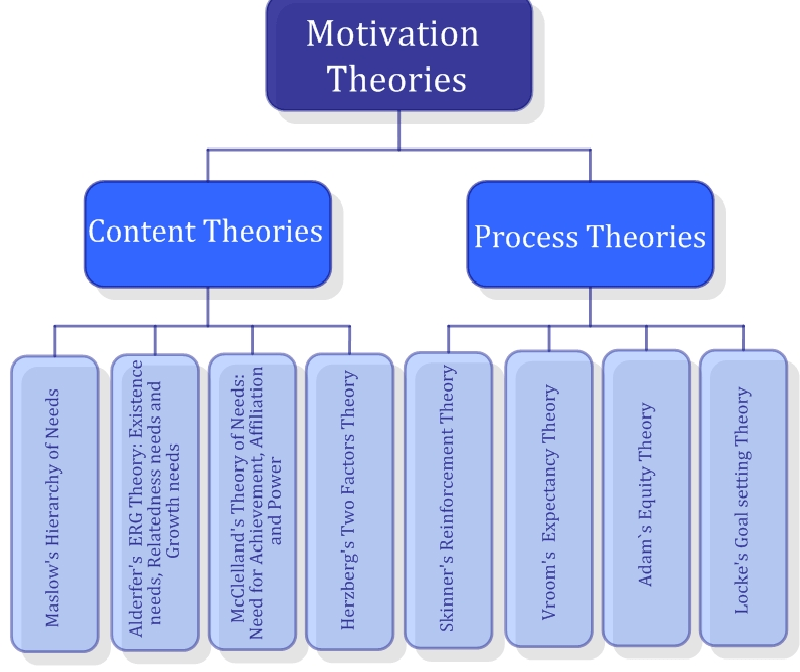

The diagram above summarizes what “everyone wins” could mean:

- Organizations win because costs are reduced (Maslow’s Hierarchy upright)

- Individuals win because each can be creative within the boundaries imposed by nature, not man / machine (Maslow’s Hierarchy upside down)

- Humanity and the machine both win because they learn from one another, adapt to each other and the world that encompasses them both (Maslow’s Hierarchies – upright and upside down)

No doubt these are topics for many future posts…