A syllogism about power:

- Human social systems / institutions are hierarchical and concentrate power at the top of their structures

- “Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely” – Lord Acton

- Human social systems / institutions will inevitably become corrupt

Why?

The answer is rooted in the interplay between our basic instincts for survival coupled with our evolved reasoning capabilities as Homo sapiens. Our advanced thinking capacity provides us with the ability to make choices whether to spend, save, keep, or give of our time, talent, skill, experience, insight, and energy. Like most animals, we care for ourselves by spending for what we need in the moment yet saving some for later in the event we need it. However, only humans have the option to accumulate and keep more than is ever needed or give the excess to others who are less fortunate so that their needs are covered as well. While the “spend and save” dichotomy is fundamental within many animal species, the “keep and give” dichotomy resides solely in the realm of higher reasoning exhibited by Homo sapiens.

Having the chance to acquire more than what is needed is a compelling motivation to discover and exploit opportunities. But what if discovery, exploitation, and gain from opportunities deprive others of similar opportunities? Or what if the consequences are even direr in that not only do others have no opportunities to do similarly, but their basic survival is at risk?

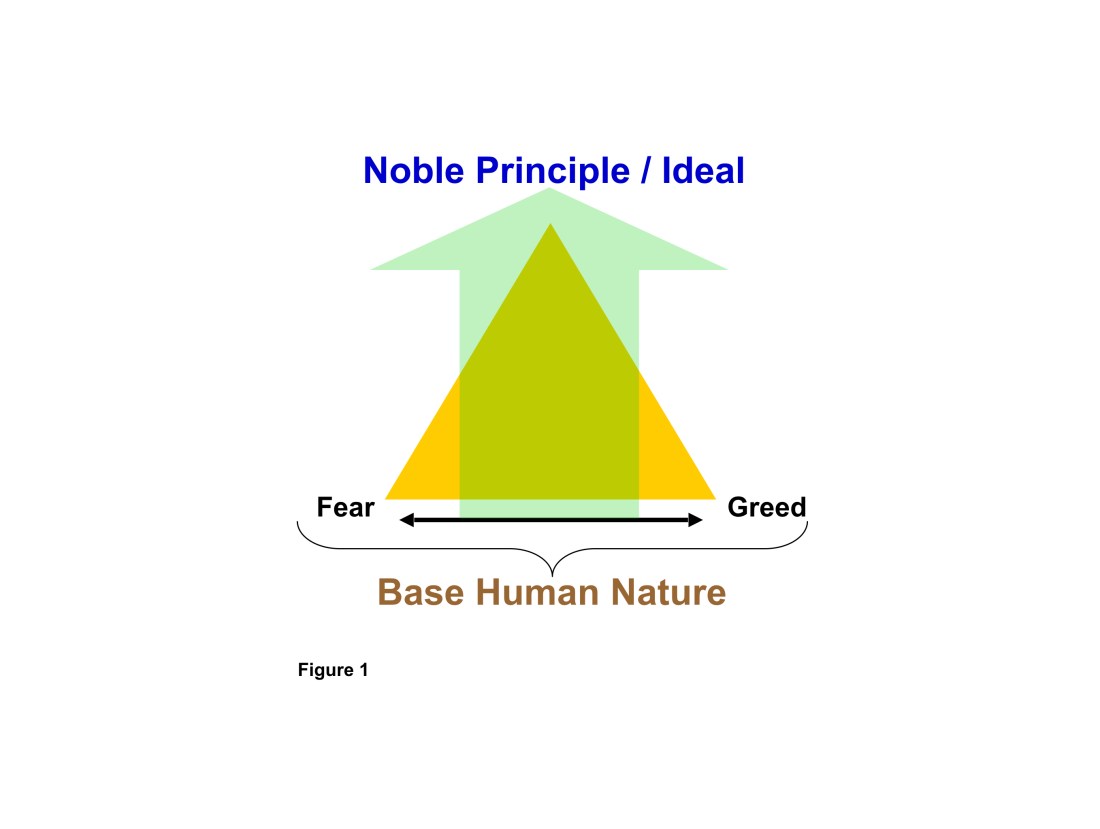

The “keep and give” dichotomy becomes a double-edged sword. On the one hand, human intelligence provides the means by which we can make or take more than we need. On the other hand, this same intelligence gives us the insight to heed a noble principle or ideal and choose to give what we have made or taken, yet do not need, to others whose survival is at stake. This is a difficult choice. For many who are caught up in the fast track of making and taking, to give does not feature very prominently and greed sets in. For others, it is not the rush to accumulate more that drives them, but quite the opposite – the fear of loss and being put into a situation where there is not enough to survive. Regardless, too many burn up their worth as creative and innovative human beings along the fear-greed continuum.

Figure 1 above illustrates a simple hierarchical social system formed by the three basic cornerstones: fear – greed – principle / ideal. Over time, however, the triangle shrinks in height until the principles and ideals that were so sterling and compelling at the outset become lost in a sea of the platitudinous and pedestrian and their relevance and influence are lost. Hierarchy, mired in the mud of fear and greed, has little nobility; it is corrupted.

Any hierarchical social system begins with a balance of principles and ideals worthy of aspiration and hope linked to the daily realities associated with fear and greed. A social system framed by such noble thoughts seeks to give all a better life. The preamble to the Constitution of the United States offers an example of these worthy ideals framing the social system of a nation:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

What really happens, though?

A syllogism about corruption:

- Corrupt human social systems benefit their ruling minorities at the expense of their ruled majorities

- Ruling minorities make rules that preserve their social systems and concentrate power further

- Corrupt human social systems insulate their ruling minorities from their ruled majorities

Beginning in 2003, there occurred numerous instances of abuse and torture of prisoners held in the Abu Ghraib Prison in Iraq (aka. Baghdad Correctional Facility), by personnel of the 372nd Military Police Company, CIA officers and contractors involved in the occupation of Iraq.

An internal criminal investigation by the United States Army commenced in January, 2004, and subsequently reports of the abuse, as well as graphic pictures showing American military personnel in the act of abusing prisoners, came to public attention the following April, when a 60 Minutes news report (April 28) and an article by Seymour M. Hersh in The New Yorker magazine (posted online on April 30 and published days later in the May 10 issue) reported the story.

The resulting political scandal was said to have damaged the credibility and public image of the United States and its allies in the prosecution of ongoing military operations in the Iraq War, and was seized upon by critics of U.S. foreign policy, who argued it was representative of a broader American attitude and policy of disrespect and violence toward Arabs. The U.S. Administration and its defenders argued that the abuses were the result of independent actions by low-ranking personnel, while critics claimed that authorities either ordered or implicitly condoned the abuses and demanded the resignation of senior Bush administration officials.

”In Address, Bush Says He Ordered Domestic Spying” by David E. Sanger, NY Times, 18 December 2005:

WASHINGTON, Dec. 17 – President Bush acknowledged on Saturday that he had ordered the National Security Agency to conduct an electronic eavesdropping program in the United States without first obtaining warrants, and said he would continue the highly classified program because it was “a vital tool in our war against the terrorists.”

In an unusual step, Mr. Bush delivered a live weekly radio address from the White House in which he defended his action as “fully consistent with my constitutional responsibilities and authorities.”

He also lashed out at senators, both Democrats and Republicans, who voted on Friday to block the reauthorization of the USA Patriot Act, which expanded the president’s power to conduct surveillance, with warrants, in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks.

The revelation that Mr. Bush had secretly instructed the security agency to intercept the communications of Americans and terrorist suspects inside the United States, without first obtaining warrants from a secret court that oversees intelligence matters, was cited by several senators as a reason for their vote.

”Katrina’s Racial Wake” by Salim Muwakkil, In These Times, 7 September 2005:

Hurricane Katrina and its disastrous aftermath have stripped away the Mardi Gras veneer and casino gloss of the Gulf Coast region, and disclosed the stark disparities of class and race that persist in 21st century America.

The growing gap between the rich and the poor in this country is old but underreported news – perhaps in part because so many of the poor also are black. Accordingly, many Americans were surprised that most of the victims of the New Orleans flood were black: Their image of the Crescent City had been one of jazz, tasty cuisine and the good-natured excesses of its lively festivals.

Where did all those black people come from, they wondered; and where were the white victims?

African Americans make up about 67 percent of the population of New Orleans, but clearly they were disproportionately victimized by the hurricane and its aftermath. And while blacks make up just about 20 percent of those living along the Gulf coast of Mississippi, their images dominated media representations of the victims there as well. In addition to race, the common denominator between blacks in both states is poverty. The “Big Easy,” has a poverty rate of 30 percent, one of the highest of any large city. The state of Mississippi has the highest percentage of people living in poverty of any state and the second-lowest median income. The state’s Gulf Coast experienced an economic boom when casinos were legalized in the early ’90s, but that new affluence did little to ameliorate the race/class divide that has deep roots in the region.

Among other things, the monster storm blew away the pretense that race has ceased to matter in the United States. Media coverage of this major disaster has made it clear that poverty and race are highly correlated.

Katrina also unearthed other uneasy truths; including the glaring ineptitude of the federal government, the domestic consequences of the illegal Iraqi invasion and the media’s proclivity to employ racial stereotypes.

Critics complain that the overwhelming blackness of the victims may have been a factor in the government’s apparent slowness to respond. In a reflection of popular black opinion, hip-hop artist Kanye West went off-script during an NBC benefit concert for Katrina victims and declared, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.”

How did we get to this?

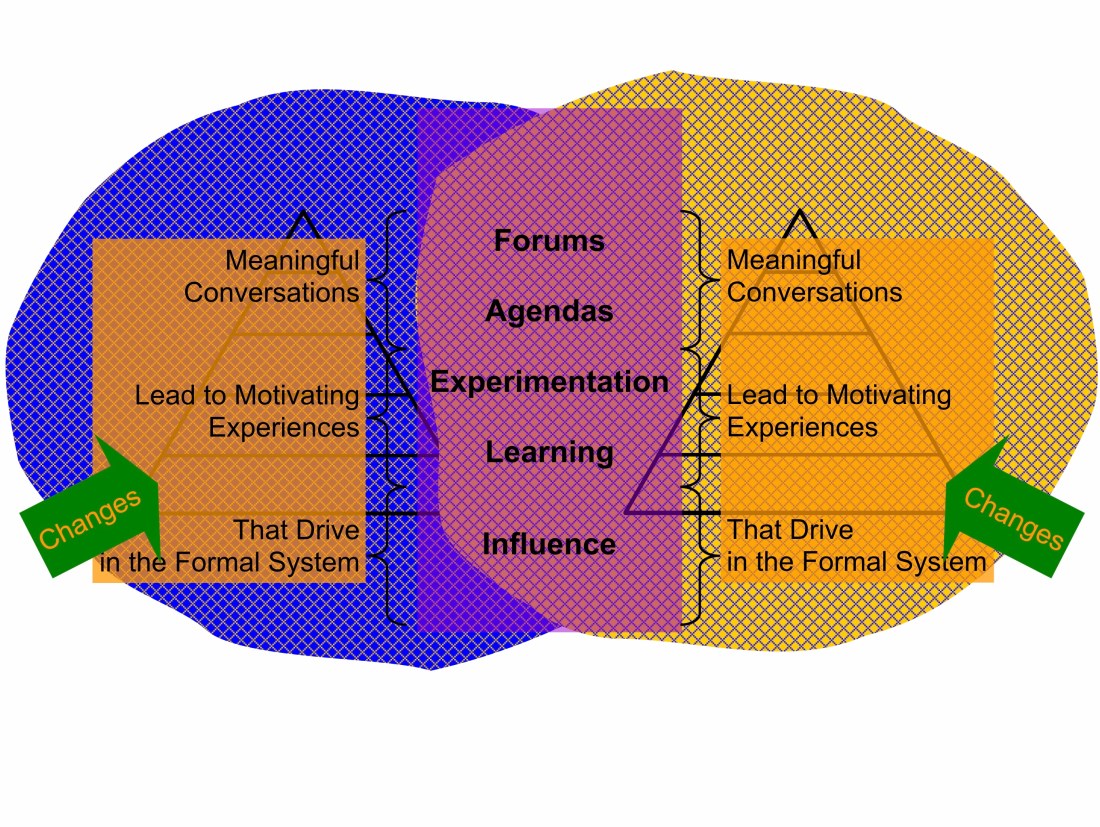

Hierarchical social systems are in a continual state of flux. Figure 2 above introduces some of these dynamics. These systems begin with lofty ideals and noble principles. This is the realm of the abstract, intangible, and philosophical where people in relationship to people posit their aspirations, dreams, thoughts, and feelings from which they describe and envision a better reality.

Such ideals do not remain in a pristine and unchallenged state. Like the people who populate them, social systems have basic needs / resource requirements that must be met in order for them to function. These resources have to be extracted / exploited and converted / deployed so the system can utilize / consume them. In other words, people in relationships to “things” make the system function and, hopefully, engage in behaviors that put the vision into practice.

People have different motivators that prompt their participation in a social system. Some are engaged by an envisioned end state constructed through relationships to people. Others are compelled by their relationships to things – the anticipation of rewards for contribution or a sense of obligation. Moving from vision to action puts the social system on a slippery slope toward compromising its values. Corruption sets in as anticipation of rewards gives way to greed, a sense of obligation succumbs to abject fear, and guiding principles fade from view.

However, the intention people have for a social system is to remain within the middle – a “dynamic balance zone” – where forces from the less evolved side of human nature that drag the system into the clutches of a fear-greed continuum are matched by forces resulting from new personalities and structures in the system that renew the vision and exalt the ideals once again. This dynamic balance zone is where relationships to people and things are positioned within a broader, more “ecological” context. Such positioning enables members of the system to take responsibility for the effect their actions have on others in the system and be held accountable for the consequences of their behaviors overall.

And that means what?

A syllogism about change:

- Corrupt human social systems are vulnerable to change

- Subversive groups form within ruled majorities, gain power, and force agendas of change on the ruling minorities

- Corrupt human social systems are supplanted

A human social system is corrupted through the increased infatuation of its members in their relationships to things rather than their relationships to themselves and others. This love of the material immerses people in the fear-greed continua and distances people from one another. This distancing is a critical determinant of how the social system will function because it establishes a condition where the consequence of one’s behavior on others is not directly experienced. In other words, there is an isolation / insulation of people in the ruling minority from the ruled majority. This breakdown in causality might be useful in the military where commanders issue orders that put soldiers in harm’s way in an effort to attack or defend. In a social system where the general health and well-being of members is contingent on socially responsible and ecologically balanced actions such a breakdown can lead to disastrous outcomes if the ruled majority pursues countermeasures; e.g., Barbara Bush:

The degree of corruption is offset by degree of affiliation. Just as getting mired in fear and greed isolates people from one another, the formulation, articulation, and pursuit of a noble principle / ideal brings people together. No meaningful collective action can occur without people first agreeing on what they want to have happen as a result – envisioning a future worth achieving.

Figure 3 above illustrates these two counter-balancing dynamics: on the one hand, more fear and greed, more corruption; more principles and ideals, less corruption; and, on the other hand, more principles and ideals, more affiliation; more fear and greed, less affiliation. Of course, in a complex system these dynamics are playing out continuously and in a highly unpredictable manner. The only assurance we have is that there are as many or more ways to affiliate with others for mutual benefit across the community as there are opportunities to engage in the pursuit of sheer material gain. It is a question of balance for each of us and to realize that the operation of the whole requires both. How DO we stay centered? Well now, that is THE question!

Originally posted to New Media Explorer by Steve Bosserman on Friday, December 23, 2005