Food is an essential requirement for life. A certain degree of psychological preoccupation is prompted if there are risks associated with getting the need for food met. As a result, securing food is one of the fundamental building blocks in Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs.”

Distance from the source of food is a sticky wicket for food consumers. We are left in the hands of government regulations, enforcement agencies, businesses, and various special interest groups in between us and the food we need for survival, health, and well-being. Questions range from plant and animal genetics to methods of production, processing, and preparing foods, to the logistical systems that transport, store, and stock what we eat as it moves from the point of production to the point of consumption.

So how far is it from the point of production to the point of consumption? According to a 2003 study, “Checking the Food Odometer: Comparing Food Miles for Local versus Conventional Produce Sales to Iowa Institutions,” by Rich Pirog at Iowa State University it can be further than one might think. For a synopsis of Pirog’s study, please read Consumers Prefer Locally Grown Foods published by the WK Kellogg Foundation.

Drawing from Pirog’s report, Jane Black offers the following analysis in her article in Slate entitled, “What’s in a number? How the press got the idea that food travels 1,500 miles from farm to plate:” 1

All statistics, of course, are based on a series of assumptions. And Pirog is quick to point out that whether or not the 1,500-mile figure applies to everyone and everything—or how it’s been misused—it has raised consciousness about where food comes from. It sends a message: It matters what you buy, and where you buy it.

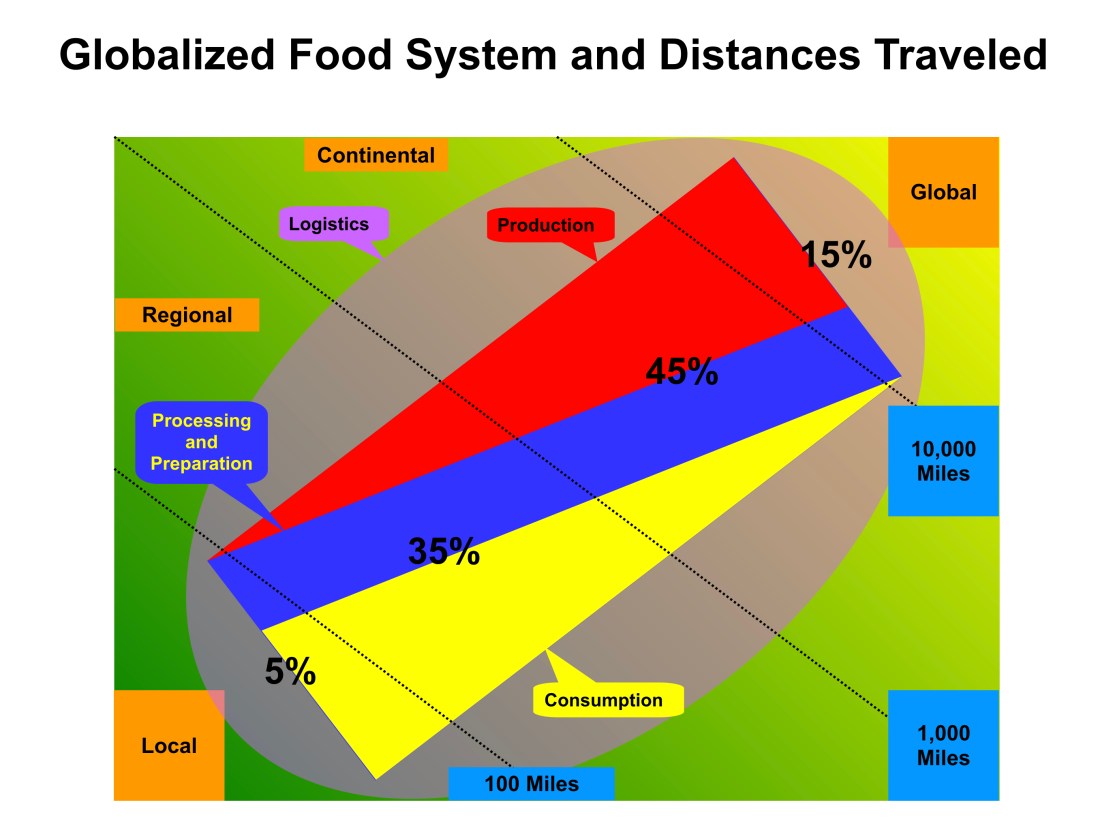

The graphic below illustrates some of the critical relationships in the current, globalized food system relative to distances food travels.

Essentially, the diagram is a continuum from local to global with regional and continental “zones” setup to offer arbitrary hash marks at the 100, 1,000, and 10,000 mile intervals in between. Clearly, the distribution of distance favors production, processing, and preparation encompassing more than 1,000 miles. Also, the interplay of production, processing and preparation, and consumption is embedded within a logistical system that supports the movement of plant and animal materials from one location to another while transferring from one production / processing stage to another.

This diagram does not attempt to quantify the complete distance traveled, but offer a way to visualize the approximate distribution of mileage when looking at the overall food system. While Pirog’s report focuses solely on fresh produce and excludes various stages of processing between production and consumption, if one included the distances incurred by these additional steps the total mileage traveled would be considerably further. Also, due to the economies of scale favored by globalized operations, processing and preparation are centralized in specific locations that enjoy advantages of lower cost labor or closer proximity to large scale production operations. This adds to total distance traveled when completing the cycle to the consumer.

In his book, PERMACULTURE: A BEGINNER’S GUIDE, Graham Burnett offers a diagram entitled, “The Industrialization of Tea” that captures the notion of distance in the globalized food system and its consequences. When the total costs of fossil fuel consumption is treated as an externality and there is relative assurance that globalized food sources are secure and can provide safe food at low cost the food system functions effectively. But what if the formula changes due to increased fuel costs? What if we cannot assure food security and safety? What is an alternative? Mr. Graham begins to explore this question by providing a second diagram, “The Permaculture Cup of Tea,” posted on the same website.

In carrying the philosophy of a “permaculture cup of tea” further, the diagram below follows the same general format as the previous graphic, only the food system is more localized than globalized.

Now, 60 % of the food system functions within an area under 1,000 miles of the point of consumption. While this stops far short of 100% under 1,000 miles, it does suggest that simply moving a mere 30% of the total food system output from over 1,000 miles to under will have a profound impact on the issues like fuel consumption, food security and safety, and community sustainability, health, and well-being. But how much difference would this really make?

While there are no data to tell us for sure, there are reports from studies in related fields that offer some insight. In The New York Times article by Matthew Wald published December 30, 2006 entitled “Travel Habits Must Change to Make a Big Difference in Energy Consumption,” the author states,

…picking a large sport utility vehicle that goes two miles farther on a gallon of gasoline than the least-efficient SUV’s would have an impact on emissions of global warming gases about five times larger than replacing five 60-watt incandescent bulbs. The dollar savings would be about 10 times larger. And the more-efficient light bulbs would have a negligible effect on oil consumption.

This suggests that shifting the 30% of the current food system activity to under 1,000 miles from the point of consumption would make a substantial difference.

There is a business case in this for sure; but how would one go about putting the business model together that leads to viable business plans and startups in localized agriculture? The key is in designing a framework that ties the critical elements of food production, processing and preparation; renewable energy and environmental remediation; logistical systems; and community sustainability together into a set of dynamic, interactive, and adaptive relationships. And that will be the topic for subsequent postings…

Wishing you all the very best in 2007!

Originally posted to New Media Explorer by Steve Bosserman on Tuesday, January 2, 2007

- The original article, “The Issues: Buy Local,” is no longer available online ↩