My previous post, Conjoined Economies, pointed out how despite the importance of parity between a time-based economy and a money-based economy for the health and well-being of community members, the money-based economy maintains a dominant presence within most social systems. Because of that imbalance, it is essential to bring time-based economy activities out of the shadows and acknowledge their value.

Timebanking provides opportunities for communities to make the time-based economy more explicit at a local level and a stronger partner with (or worthy opponent to) the predominant money-based economy, globally.

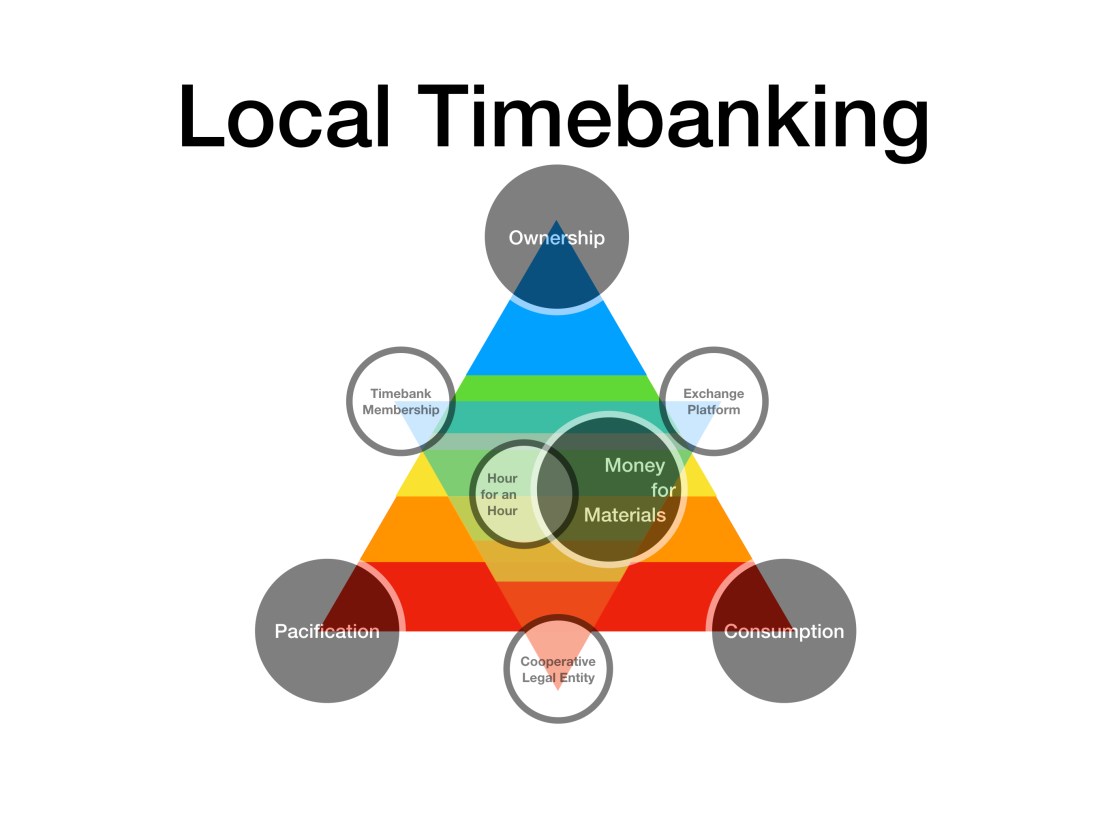

The diagram below illustrates how the two economies would relate to one another on more local (smaller circumference) and global scales.

While the organizing principles for a time-based economy are similar, those defining timebanking have several key characteristics, namely: “participation” becomes membership with an account in a timebank; “exchange” becomes use of a specific exchange platform; and “commons” relates to a cooperative or otherwise legal entity as a governance structure. In addition, the general concept of time as the driver for economic activity shifts to more specific notion of an hour of service for an hour of credit.

Timebanking Core Values

TimeBanks USA, founded by Edgar Cahn in 1995, offers a complete package of operating philosophy, materials, software, and support for communities to get involved in timebanking. As an example, below are The Five Core Values of TimeBanking initially stated by Cahn: 1

- Asset: Every one of us has something of value to share with someone else.

- Redefining Work: There are some forms of work that money will not easily pay for, like building strong families, revitalizing neighborhoods, making democracy work, advancing social justice. Time credits were designed to reward, recognize and honor that work.

- Reciprocity: Helping that works as a two-way street empowers everyone involved – the receiver as well as the giver.

The question: “How can I help you?” needs to change so we ask: “Will you help someone too?” Paying it forward ensures that, together, we help each other build the world we all will live in.- Social Networks: Helping each other, we reweave communities of support, strength & trust. Community is built by sinking roots, building trust, creating networks. By using timebanking, we can strengthen and support these activities.

- Respect: Respect underlies freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and everything we value. Respect supplies the heart and soul of democracy. We strive to respect where people are in the moment, not where we hope they will be at some future point.

Note the similarity of the five Core Values to Jay Walljasper’s interpretation of the eight design principles Elinor Ostrom defined for effective governance of the commons quoted in Organizing Principles for a Time-Based Economy.

Timebanking – The Realized Value of Unpaid Time

In accordance with these Core Values, the timebank becomes a venue in which any member has the opportunity to take greater responsibility for unpaid time by doing the following:

- Document unpaid time in a personal member account

- Convert unpaid time into a currency according to a rate shared by all members

- Exchange unpaid time in account for access and usage of resources offered by other members

Timebanking – Benefits

Of course, realizing the value of unpaid time is more about building relationships within local communities than conducting transactions. hOurworld, a self-described “…international network of neighbors helping neighbors,” defines the timebank venue as a place where

Members share their talents and services, record their hours, then ‘spend’ them later on services they want. Everyone’s hours are equal. There is no barter. These are friendly, neighborly favors. Together we are restoring local community currency based on relationships.”

The Hour Exchange Portland lists the benefits of an exchange as follows:

- Trusting relationships – (trust, reciprocity and civic engagement)

- Greater access to goods and services

- Employment references

- Stronger informal support systems

- Safety in neighborhoods

- Increased self-esteem / confidence

- Greater participation in community events

- Diminished loneliness

- Accept help with dignity – knowing you’ll help others in return

- Building social capital in neighborhoods — Robert Putnam 2

These descriptions of timebanking core values and benefits of an exchange certainly speak to how timebanking can help us progress toward the goals:

- Legitimize time-based economy behaviors

- Expand symbiotic / synergistic coverage by both the time-based and money-based economies

But there is so much more that timebanking offers as well as numerous platforms, processes, currencies, etc. at work to bring the time-based economy into its rightful position of parity with the money-based economy. Look to future posts that take deeper dives into timebanking and explore the topical landscape of complementary currencies, peer-to-peer relationships, systems change theory in practice, etc. more broadly.

- The Five Core Values of TimeBankingEdgar Cahn is the founder of modern timebanking. He noticed that successful timebanks almost always work with some specific core values in place. In his book No More Throw-Away People, he listed four values. Later, he added a fifth. These have come to be widely shared as the five core values of timebanking – and most timebanks strive to follow them. They are a strong starting point for successful timebanking. ↩

- Smith, M. K. (2001, 2007) ‘Robert Putnam’, the encyclopaedia of informal education, www.infed.org/thinkers/putnam.htm. Last update: May 29, 2012. ↩